How the Efficiency for Access Design Challenge Has Helped to Empower Young People in the Energy Access Sector

As the impacts of climate change increase, it is now more important than ever that young people are empowered to help accelerate clean energy access. One way in which to engage young people is through sector-led incentives, such as the Efficiency for Access Design Challenge

By Eleanor Wagner, Marketing Communications Executive, Energy Saving Trust, Co-Secretariat of Efficiency for Access

This month, from 28–30th September, the COP26 youth summit will be held in Milan. As the impacts of climate change increase, it is now more important than ever that young people are empowered to help accelerate clean energy access.

One way in which to engage young people is through sector-led incentives, such as the Efficiency for Access Design Challenge. Funded by UK aid and IKEA Foundation, the Challenge is a global, multi-disciplinary competition that empowers teams of university students to create innovations that help to accelerate a just and inclusive clean energy transition.

We interviewed three teams from 2020–2021’s Challenge to find out how the competition helped to engage them, and what other young people can do.

What was your proposed design for the Efficiency for Access Design Challenge and how did it benefit the lives and livelihoods of people living in an off-grid environment?

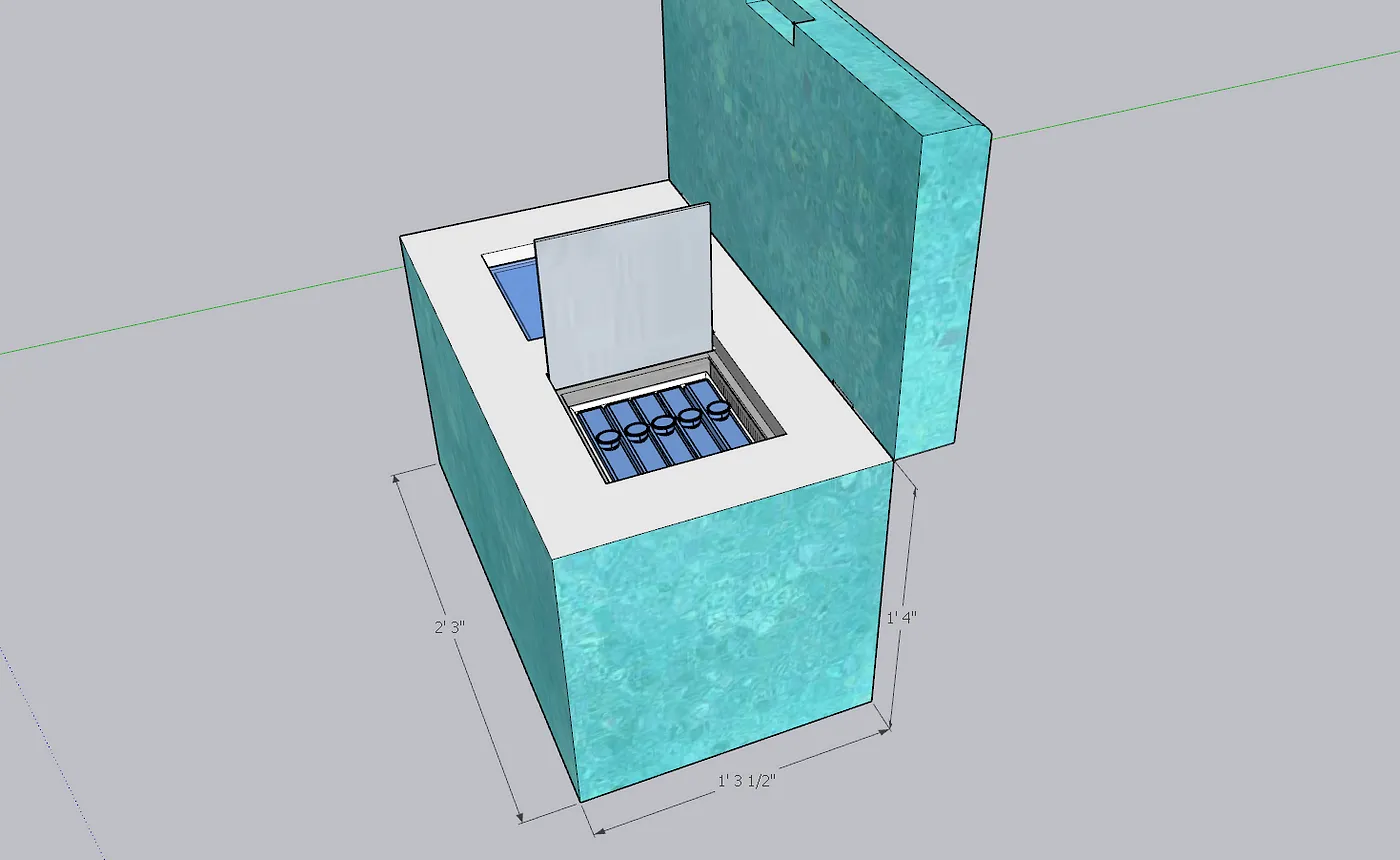

Sadik Abdal, Team 2020–03, Independent University, Bangladesh : Our proposed design for the Efficiency for Access Design Challenge was a solar direct drive vaccine refrigeration and effective cold chain system. We aimed to create an off-grid vaccine refrigeration system that was capable of storing vaccines at optimum temperatures between 2°C to 8°C (35°F to 46°F) in off-grid regions in rural Bangladesh. The device works by harnessing and storing the power of solar renewable energy in the form of ice banks, without any requirement for batteries. Our project was aimed at tackling the issue of immunising people in off-grid regions experiencing refugee crises, such as the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh. We also aimed to help the storage of perishable items with short shelf-lives in off-grid regions.

Joshua Mwesiga, Team 2020–07, Makere University : We proposed a hybrid solar grain dryer that uses both direct solar energy and DC power from a battery, connected to photovoltaic cells. We sought to reduce drying time, improve seed quality and eventually increase income for small scale farmers in rural Africa. With improved seed quality, farmers earn more income from their produce, while increasing time for other productive activities as a result of the reduction in drying time offered by our design.

Souryadeep Basak, Team 2020–12, TERI School of Advanced Studies: We designed a solar powered hydroponic fodder unit, to provide a base income to the communities affected by agricultural difficulties. Climate unpredictability, poor crop prices, erratic rainfall, soil acidity and degradation are some of the reasons for the farmer suicide epidemic in India. While most of these communities own livestock, their productivity and revenue generation is marginal, due to lack of land and lack of access to green fodder.

There is a great degree of correlation between off-grid areas and regions dependent on livestock as income streams. Therefore, this affordable solution can serve as a safety net for underserved communities in need. Integration of widows and disabled people in daily operations upholds the UN pledge to ‘leave no one behind’. The automation and control circuitry makes it operation friendly and maintenance can be carried out on-site by locals.

Why is accelerating energy access important?

Sadik Abdal: Our team strongly believes in the idea that access to sustainable, clean and affordable energy should be a basic human right. Accelerating energy access throughout the world, especially in rural regions should be a priority for engineers and lawmakers. It is an effective tool to tackle growing inequality and accelerate technological advancements.

What do you see as your role, and the role of other young people, in helping to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030?

Joshua Mwesiga: Our role as young people is to be ambassadors and advocates for Sustainable Development Goals in our communities. This can take the form of educating people in our communities about the goals, for example, highlighting the benefits and the requirements to achieve those goals. We also have to lead the way in coming up with innovations that will facilitate sustainable existence.

What did you learn from creating a prototype with the funding from the IKEA foundation?

Souryadeep Basak: Prototyping was the most illuminating part of the journey for me. Although as an engineer, I have often committed designs to paper and simulation, this opportunity enabled me to fabricate and design a prototype myself. It was a steep learning curve, from designing control system electronics, shopping for electrical and mechanical parts amid a pandemic, setting up solar panels to optimising the power condition unit and validating the design through climate simulations. This very intensive learning process gave us greater confidence regarding our design and its reliability.-

The IKEA Foundation has been an incredible support throughout the entirety of the Challenge, not only with their support for building our prototype, but also helping us understand the true potential of our project.

Sadik Abdal: Jeffrey Prins, who was present during our final pitch, also gave us a lot of useful insights towards the usefulness of building an actual physical prototype rather than just designing the project. He also made noteworthy remarks about product life-cycle and diversifying the end products to achieve a wider range of end-users which really resonated with our team.

Do you have any advice for young people looking to engage in the off-grid energy sector?

Joshua Mwesiga: My advice is that they should take a dive into the sector as soon as the thought of joining the sector crosses their mind. This nascent sector provides a wide range of long-term opportunities and gives a platform for the sector players to impact many lives. Organisations like Efficiency for Access provide comprehensive information for anyone looking to kickstart their journey in this sector.

What key lessons will you take from the Efficiency for Access Design Challenge into your future career?

Souryadeep Basak: I believe the comprehensive experience was one of a kind and the insight I gained from the process made me very confident about my prototype. The webinars and mentorship meetings helped to steer our ideas into a crystalline from, while experimentation and documentation provided real-time validation of our design. Most importantly, the holistic encapsulation of idea to product is a skill that is transferable to all projects in the future. That, I believe, is my greatest takeaway from this collaborative experience.

Sadik Abdal: Always have a mentor. Interactions with our mentor saved us a significant amount of time on the tasks we performed and we leveraged our mentor’s experiences through their advice, which made us more productive and efficient.

As a result of the Efficiency for Access Design Challenge, Souryadeep Basak decided to pursue a PhD to take his project further.

Could you tell us about your PhD and how the Efficiency for Access Design Challenge helped you on your journey?

The Efficiency for Access Design Challenge pushed me to scale up my prototype as part of my PhD research. In a nutshell, I am attempting to create modular hydroponic vertical farms inside retrofitted shipping containers. The purpose is to make energy efficiency the primary design constraint, to make the unit versatile in all climate zones, while ensuring minimum distance between production and consumption, minimal water use, no pesticides and local employment.

While the container farm forms the bulk of my PhD research, I will be simultaneously adapting my fodder unit design to be operated as a paddy nursery, which can be used in several coastal regions of India. Observation of the fodder unit and seasonal operation as a paddy nursery will be a feedback process with data collection and analysis over a period of 12 months. I sincerely hope that the final design shall be able to contribute to impactful sustainable development.